Supporting Monarch Populations in Urban Areas and Campuses – A Comprehensive Guide

Introduction: Feel free to skip this section if you’re just here for the guide.

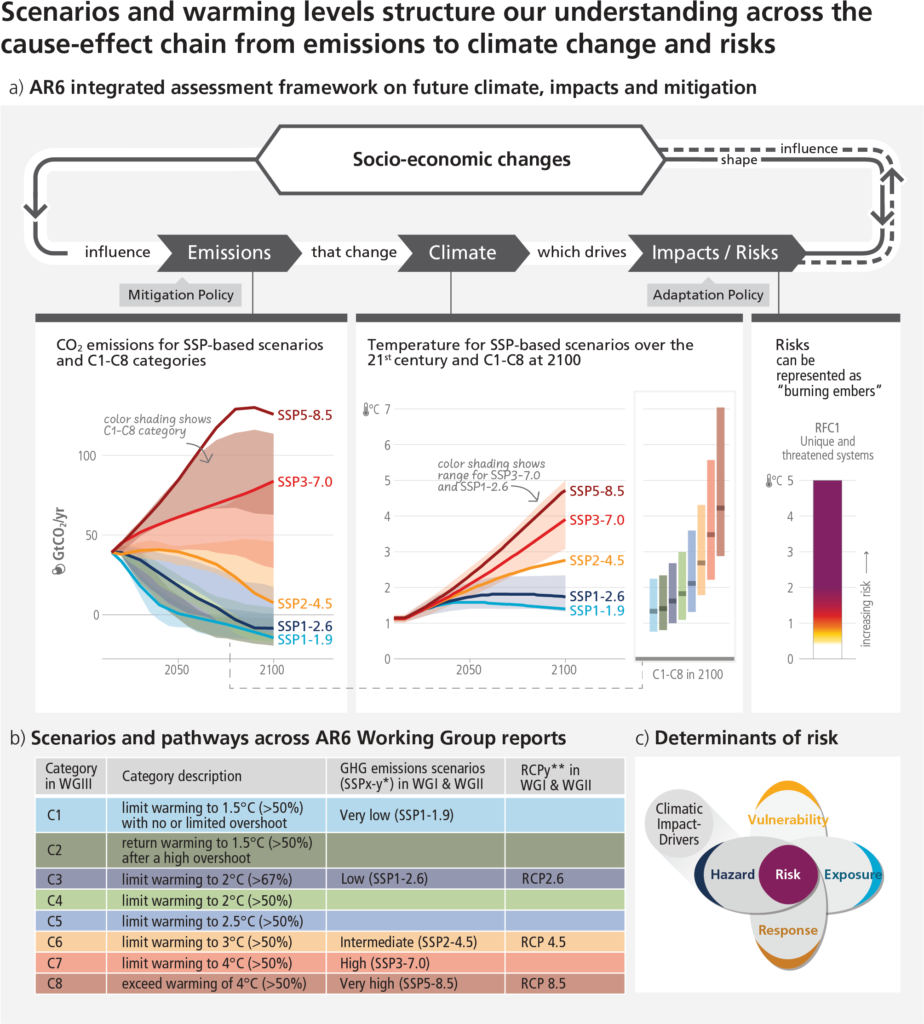

Under the Trump administration, protections for ecosystems and endangered species are being revoked in favor of rapid industrialization. The impacts of these policy changes can be predicted using SSP-based temperature or emissions projections charts. These charts predict future greenhouse gas concentrations, global temperature increases, sea level rises, and the frequency of extreme weather events under five different scenarios.

The best scenario, SSP-1 (The Green Road), is a future that focuses on sustainability, equal access to education, fair wages, strict protection of the environment and species, and low material consumption. The worst scenario, SSP-5 (Fossil-Fueled Development), is a future that is heavily dependent on fossil fuels, adheres strictly to capitalism, experiences rapid technological progress, and allows for the unregulated use of natural resources. As of this year, 2025, the United States is rapidly shifting towards SSP-4 (Inequality). This paper from the Journal of Global Climate Change best defines this scenario.

“Highly unequal investments in human capital, combined with increasing disparities in economic opportunity and political power, lead to increasing inequalities and stratification both across and within countries. Over time, a gap widens between an internationally-connected society that contributes to knowledge- and capital-intensive sectors of the global economy, and a fragmented collection of lower-income, poorly educated societies that work in a labor intensive, low-tech economy. Social cohesion degrades and conflict and unrest become increasingly common. Technology development is high in the high-tech economy and sectors. The globally connected energy sector diversifies, with investments in both carbon-intensive fuels like coal and unconventional oil, but also low-carbon energy sources. Environmental policies focus on local issues around middle and high income areas.”

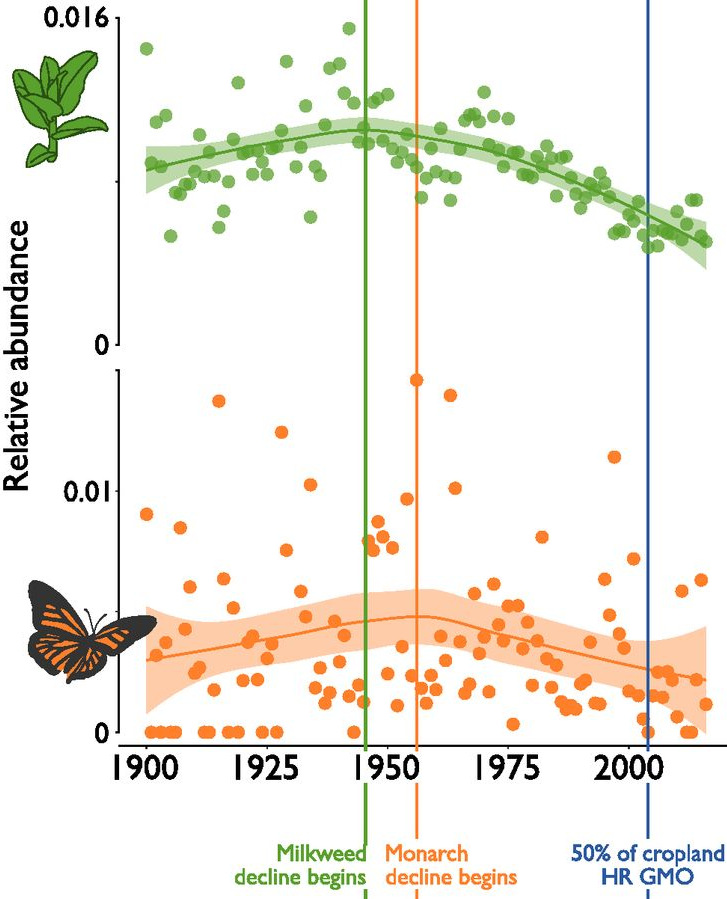

Given the predictions shown in the SSP chart, greenhouse gas concentrations will increase significantly, and global temperatures will rise 2°C by 2050 (compared to pre-industrial levels). This would spell disaster for global environments and overall biodiversity. Monarch butterflies (Danaus plexippus) are particularly sensitive to changing temperatures, as their migration pattern is contingent on milkweed’s growth and temperature changes across regions. As summers become longer and hotter, winters become shorter, and cold weather becomes erratic, their migratory instinct will change. It’s predicted that there will be delays in their migratory patterns due to the warmer temperatures, and they will arrive at overwintering sites later. Milkweed distribution will also change, as their propagation is based on temperature—both Monarchs and milkweed prefer temperate climates, with temperatures between 65°F and 85°F. Milkweed populations will likely move northward, causing Monarchs to fly further distances during breeding periods.

The Trump administration has repeatedly taken actions that would go against the best interests of the lower classes and the environment: defunding of the education system, revocation of environmental protections, a nationwide market crash, instatement of celebrities and CEOs into government positions, cutting of federal Medicaid funding, increased policing against legal and illegal immigrants, distmanteling of the National Park System, defunding and dismantling of envirnmental protection agencies (EPA, NOAA, FWS, Department of the Interior, State Energy Program, Weatherization Assistance Program, etc.), and the list could go on. The most relevant change to this guide is the proposed overhaul of the Endangered Species Act. This overhaul would limit its ability to protect endangered and threatened species and ecosystems. It also proposes changing the definition of “harm,” which is typically interpreted as any action that could harm the environment directly or indirectly. This change would effectively allow industries to implement projects that harm ecosystems and species, such as quarry mining, which involves using explosives to extract minerals and other desirable materials. In 2024, it was proposed that the Monarch Butterfly be added to the endangered species list, creating federal protections for them and their habitats. If this proposed overhaul were implemented, then any protections allocated by the Endangered Species Act would be null, and their populations would continue to decline rapidly.

When the federal government fails in its duty to protect its people and land, citizens must take on that responsibility in its stead. Unfortunately, you can’t solve every problem at once—and this guide focuses specifically on supporting Monarch Butterfly populations. But, in the face of the federal government’s willful neglect of one of the nation’s most beloved and iconic species, this is one problem with clear and achievable solutions: create your own habitats.

Native Milkweed Species and Declines

Over the last few decades, the United States, Canada, and Mexico have lost over one billion milkweed stems due to urbanization and urban renewal, the process by which unused agricultural fields and woodlands are redeveloped for residential, industrial, or commercial use. This is land that would have previously been in the ideal stages of ecological succession, maintaining high population densities of shrubs, tall grasses, and flowering plants such as milkweeds. This disappearance of milkweed directly correlates to the population declines in Monarchs — the reduction in suitable habitats has forced them to inhabit smaller areas, increasing competition for milkweed. In turn, this causes individual milkweed plants to carry more eggs than they can feasibly sustain without being completely destroyed.

There are over one hundred different species of milkweed, only about thirty of which are consumable by monarch caterpillars. For the most part, there are nine native species you are likely to encounter in the Northeast region, and not all of these species have overlapping ranges. You can purchase milkweed seeds from a variety of sources, and there are even Monarch Conservation Organizations that will provide them for free. There are generally two variations of milkweeds available for purchase: wild types and cultivars. Wild types are, as the name suggests, genetic varieties that would be found in the wild. Cultivars, on the other hand, are bred specifically for desirable traits, such as color or flower yield, and are most often used in gardens for their combination of ornamental and ecological value. For example, see the two varieties of Swamp Milkweed below. Swamp Milkweed typically only comes in vibrant pink or purple; however, the cultivar species, Ice Ballet Swamp Milkweed, is a bright white. These differ from genetically modified organisms (GMOs), which have been genetically engineered in a laboratory for specific characteristics.

There is a certain stigma associated with cultivars, as they are likely to pass their modified genetics to wild populations; however, this is not a significant concern within urban gardens, as the probability of crossbreeding is low. There is also concern over their ability to functionally provide suitable nectar and pollen for pollinators, which is true for some cultivars. Certain cultivar milkweed plants have had alterations to their flower production, meaning they produce more flowers on average per cluster. This effectively hinders their reproductive systems and decreases nectar and pollen availability. This, however, is not something to be overly concerned with, as studies have shown that monarchs will pollinate, oviposit, and consume nectar at the same rate as wild types. Their widespread availability and enhanced phenotypical genetics make them an excellent choice for urban gardens.

This information primarily comes from the Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Database. Also, see this simplified guide for more detailed information on plant structures, as well as the provided chart of flower cluster types. I’ve also provided a short and straightforward guide to identifying soil characteristics; it includes two methods (see Garden Setup section).

Common Milkweed (Asclepias syriaca)

Range: True to its name, this species has one of the largest native ranges of the milkweed varieties, and can be found in thirty-nine of the fifty states across four of the five regions.

Endangered Status: Very common/Not of concern

Preferred Habitat/growing conditions: Medium to fine sandy, clayey, or rocky calcareous soils. Also found in well-drained loamy soils. Needs to be planted in an area with direct sunlight.

Bloom Times: Jun – Aug

Characteristics and Identification:

- Color: White or Purple

- Average Height: ~ 5 feet

- Leaf Characteristics:

- 6-8 inches long and 2-3.6 inches wide

- Arrangement: Opposite

- Shape: Elliptic, Lanceolate, Oblong, Ovate (long, roundish, and comes to a point)

- Flower Cluster: Umbel (all the individual flower stalks arise in a cluster at the top of the central stalk and are of about equal length)

Swamp Milkweed (Asclepias incarnata)

Range: Similar to the Common Milkweed, this species has a wide range that covers most of the United States and Canada.

Endangered Status: Common/Not of Concern

Preferred Habitat/growing conditions: Moist, medium to wet clay soil. Can tolerate acidic soil. True to its name, it thrives in ponds and swamps.

Bloom Times: May – Sept

Characteristics and Identification:

- Color: Orange, Yellow

- Height: ~1-2 feet

- Leafs: 2-4 in long and 1-2 cm wide

- Arrangement: Alternate

- Shape: Lanceolate, Linear, Oblong

- Flower Cluster: Umbel (all the individual flower stalks arise in a cluster at the top of the central stalk and are of about equal length)

Butterfly Weed (Asclepias tuberosa)

Range: Another common species, it can be found in all of the Northeastern states. However, finding them in the wild is becoming increasingly rare.

Endangered Status: Endangered in NH. Possibly “extinct” in ME. Threatened in VT, RI, and NY

Preferred Habitat/growing conditions: Prefers well-drained sandy soils. Tolerates drought. Requires a lot of sunlight.

Bloom Times: May – Sept

Characteristics and Identification:

- Color: Orange, Yellow

- Height: ~1-2 feet

- Leafs: 2-4 in long and 1-2 cm wide

- Arrangement: Alternate

- Shape: Lanceolate, Linear, Oblong

- Flower Cluster: Umbel (all the individual flower stalks arise in a cluster at the top of the central stalk and are of about equal length)

Whorled Milkweed (Asclepias verticillata)

Range: This species is native to all Northeastern states except Maine and New Hampshire. Finding one of these plants in the wild is rare.

Endangered Status: Threatened in MA, RI, PA, NJ, VT, and NY

Bloom Times: May – Sept

Characteristics and Identification:

- Color: White, Green

- Height: 2-3 feet

- Leafs: 2-3 inches long and 1.5 cm wide

- Arrangement: Whorled (arranged in a ring around the stalk)

- Shape: Linear (longer than it is wide, and straight)

- Flower Cluster: Umbel (all the individual flower stalks arise in a cluster at the top of the central stalk and are of about equal length)

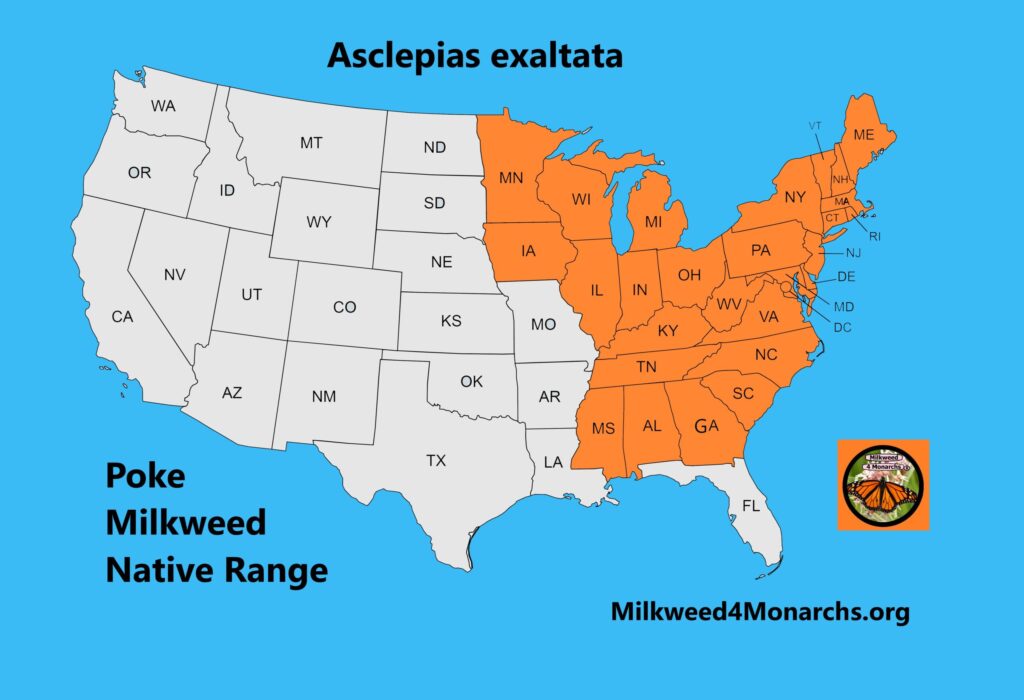

Poke Milkweed (Asclepias exaltata)

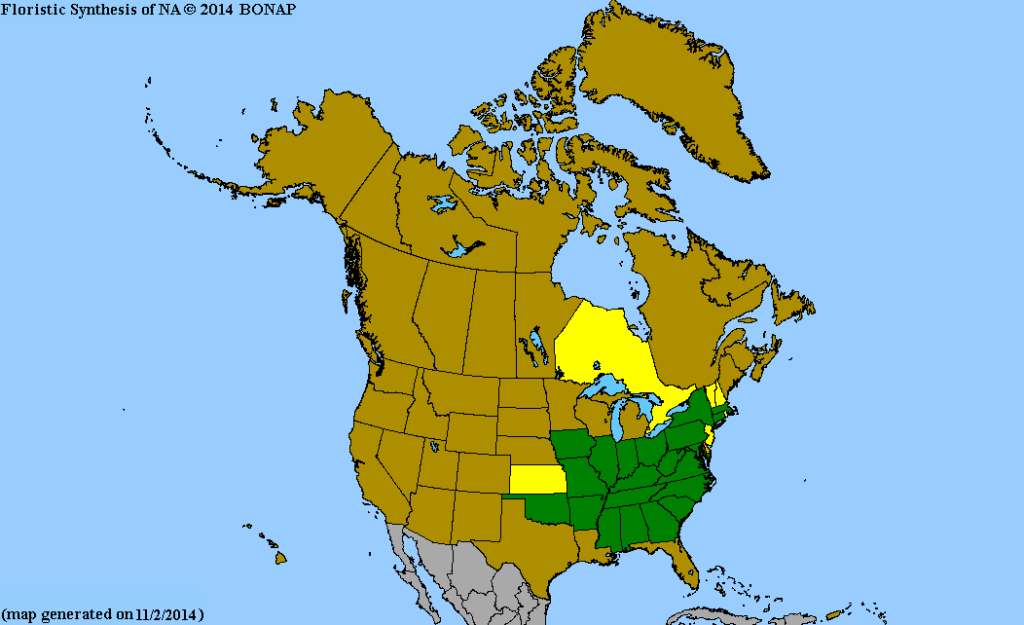

Range: This species’ native range is limited, encompassing only the upper half of the Midwestern states and the Northeast.

Endangered Status: Not of Concern

Preferred Habitat/growing conditions: Moist, loamy soil with high organic content. Prefers partial shade.

Bloom Times: May – Aug

Characteristics and Identification:

- Color: White, Pink, Green

- Height: 2-6 feet

- Leafs: 2-10 in long and 1-4 in wide

- Arrangement: Opposite

- Shape: Elliptic, Lanceolate, Ovate

- Flower Cluster: Umbel (all the individual flower stalks arise in a cluster at the top of the central stalk and are of about equal length)

Purple Milkweed (Asclepias purpurascens)

Range: This species has a broad native range and is found throughout the eastern half of the United States, except Vermont. Finding one in the wild is rare in some states.

Endangered Status: Endangered in Mass, no existing wild populations in RI.

Preferred Habitat/growing conditions: It can thrive in a variety of soils, as long as they are partially sandy and well draining. It prefers partial sun.

Bloom Times: May – Jul

Characteristics and Identification:

- Color: Purple, Red

- Height: 3-4 feet

- Leafs: 4-8 inches long and 2-3 inches wide

- Arraingement: Opposite

- Shape: Elliptic, Oblong

- Flower Cluster: Umbel (all the individual flower stalks arise in a cluster at the top of the central stalk and are of about equal length)

Fourleaf Milkweed, Asclepias quadrifolia

Range: Found across the Northeast, although it is rare or endangered in certain states.

Endangered Status: Threatened in NH and RI.

Preferred Habitat/growing conditions: Moist sandy or loamy soil. Prefers partial sunlight.

Bloom Times: May – Jul

Characteristics and Identification:

- Color: White, Light Pink

- Height: 1-3 feet

- Leafs: 1 to 6 inches long and 2.4 inches wide

- Arrangement: Opposite and Whorled. (four leaves opposite each other in a ring around the stalk)

- Shape: Elliptic, Lanceolate, Ovate

- Flower Cluster: Umbel (all the individual flower stalks arise in a cluster at the top of the central stalk and are of about equal length)

Redring Milkweed (Asclepias variegata)

Range: This species is found in almost all Northeastern states, except Maine, Rhode Island, New Hampshire, and Vermont.

Endangered Status: Endangered in CT, NY, PA.

Preferred Habitat/growing conditions: Well-draining sandy or rocky soil. Prefers partial shade.

Bloom Times: May – Jul

Characteristics and Identification:

- Color: White, Purple

- Height: 1-4 feet

- Leafs: 2-6 in long and 1/2-3 in wide

- Arrangement: Opposite

- Shape: Oval to broadly oblong-elliptic

- Flower Cluster: Umbel (all the individual flower stalks arise in a cluster at the top of the central stalk and are of about equal length)

Invasives to Avoid:

When buying full-grown flowers from nurseries, it’s best practice to quarantine them before planting to ensure that any existing pesticides, herbicides, or insecticides have worn off. This also allows you to monitor the plant for any existing parasites. And, when searching for the perfect milkweed and decorative plants for your garden, it’s essential not to choose solely based on aesthetics. While charming on the outside, particular species of plants can be deadly or harmful to Monarchs. These species, while not overtly poisonous to Monarchs, often carry diseases and predators that can negatively impact their populations and development. These are species to avoid when setting up your garden.

Black Swallow-wort (Apocynaceae Vincetoxicum) and Pale Swallow-wort (Vincetoxicum rossicum):

Black and Pale Swallow-worts are invasive species of milkweed introduced into the U.S. in the 1800s as decorative plants. Unlike other milkweed species, they contain undigestible toxins that are deadly to Monarch caterpillars: tylophorine and Antoine. These fast-growing vines can quickly spread and overwhelm garden spaces.

Characteristics:

- Color: Black Swallow-wort have dark blackish-purple flowers. Pale Swallow-wort have light pink to maroon flowers.

- Height: Up to 7 feet tall.

- Leafs: Elliptic.

- Arrangement: Opposite.

- Flowers: The flowers are flat and star-shaped, with five points that merge at the center.

Tropical Milkweed (Asclepias curassavica)

Tropical milkweed is an invasive species native to the Caribbean, South America, Central America, and Mexico. This species thrives in tropical conditions and is most commonly found in Florida, Hawaii, and California. This species is not toxic to Monarch butterflies, but it has a higher chance of containing parasites and other diseases

Characteristics:

- Color: The flowers are vibrant red, with orange or yellow interior colors. There is also an all-yellow cultivar.

- Height: Up to 4 feet.

- Leafs: Lanceolate

- Arrangement: Opposite

- Flowers: The flowers are tubular, with five sepals and five lobes

Native Nectar Plant Species:

While Monarch caterpillars are relient on milkweed, adults can have more variety in thier diets; feeding on plant nectar. Almost any species of native flower will suffice, however, there are some reccomended species listed below:

Wild Bergamot (Monarda fistulosa)

Characteristics:

- Color: Soft lavender to pinkish-purple

- Bloom Times: Mid to late summer

- Leaf Type: Lance-shaped to ovate

- Arrangement: Opposite

- Flowers: Tubular, two-lipped flowers clustered in rounded heads

- Soil and Sun: Prefers well-drained soil; tolerant of dry conditions once established. Prefers full sun.

New England Aster (Symphyotrichum novae-angliae)

Characteristics:

- Color: Vivid purple to violet petals with a bright yellow center

- Bloom Times: Late summer to fall

- Leaf Type: Lanceolate

- Arrangement: Alternate

- Flowers: Daisy-like flower heads with many narrow petals

- Soil and Sun: refers moist, well-drained soil but is adaptable to various conditions. Preferes full sun.

False Dragonhead (Physostegia virginiana)

Characteristics:

- Color: Soft pink to pale purple (occasionally white)

- Bloom Times: August to October)

- Leaf Type: Lanceolate

- Arrangement: Opposite

- Flowers: Tubular, two-lipped flowers arranged in dense vertical spikes

- Soil and Sun: Moist, well-drained soil is ideal. Prefers partial shade.

Canada Goldenrod (Solidago canadensis)

Characteristics:

- Color: Bright golden-yellow

- Bloom Times: August to October

- Leaf Type: Lanceolate

- Arrangement: Alternate

- Flowers: Tiny, daisy-like flowers in dense, arching panicles at the top of the plant

- Soil and Sun: Adaptable to a wide range of soils — prefers well-drained, average soil. Prefers full sun, but tolarates partial.

Pests, Diseases, and Poisons

Pests:

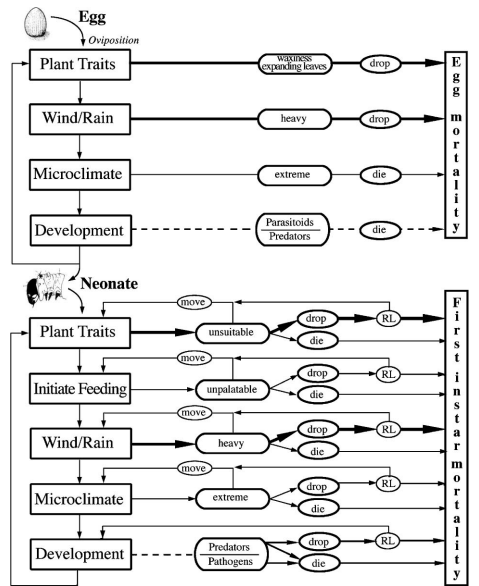

Monarchs have a variety of predators, many of which are attracted to gardens, regardless of whether they are in an urban or rural location. It’s important to remember that, no matter what defenses are put in place, there will be Monarchs that die while within your garden, and between 60% and 90% will die before reaching adulthood — the cycle of life cannot be disrupted, and unfortunately, herbivores are at the bottom of the ecological hierarchy, meaning some will have to die to maintain the natural processes and biodiversity of the area. Each species has its own role to play in maintaining the health of your garden. Remember, the goal with this section is not complete extirpation, but routine maintenance. That being said, here are the predatory species you are likely to encounter in your garden, invasive species that should be exterminated, and the dos and don’ts of preventing infestations.

Naturally, there will be losses within your Monarch ranks; however, there is a difference between a natural predator-prey relationship and an all-out slaughter. All of the species listed below, regardless of whether they are predators, prey, herbivores, carnivores, or anything in between, can experience massive population explosions. When these events occur, they disrupt the natural balance of the food chain and lower the area’s biodiversity. Take herbivores, for example. When a herbivorous species, like the common grasshopper, infest a garden, they consume all of the available vegetation. This, in turn, decreases the available food resources for other species, effectively culling their populations — i.e., a complete disruption of the food chain.

Below are the natural predators of Monarch adults and caterpillars/larvae. The incidental predators are not listed( typically, herbivorous species will not consume Monarch eggs unless they are located on milkweed leaves). The presence of these species within your garden is natural and often does not warrant immediate action. However, in the case of an infestation, remedies are also listed.

Invertebrates

Ants

Ants are categorized as opportunists, meaning they can adapt and thrive in most environments. They will likely be found in urban gardens. Monarch larvae are an easy food source for them, as they have not had the opportunity to sequester high levels of cardenolides (toxins) into their bodies. Ants will be particularly aggressive towards larvae and caterpillars due to their unique feeding system. A scout ant will search for suitable food, and once it has located a source, it will leave a pheromone trail back to the colony. A small army of ants will follow this trail back to the food source, systematically kill the defenseless larvae, and carry them back to the colony, leaving no trace of the newborns.

Given the amount of food available in gardens, a small colony of ants is likely to grow into an infestation. Therefore, it’s essential to monitor their populations closely. When removing infestations, avoid using pesticides, as they may inadvertently harm Monarch larvae and caterpillars. Listed below are some standard, insecticide-free methods of exterminating ants from your garden.

- Poison: Introducing poison to an ant colony differs from using pesticides to remove them. In this method, you should put ant poison on a food source, like a piece of bread, and leave it outside the colony. The ants will bring this back into the nest, and the poison will do the rest.

- Borax and sugar mixture: This is a true-and-tried method. It involves mixing borax powder with sugar and sprinkling it around the colony opening. Borax is poisonous and undetectable by ants, and they will be drawn in purely by the sugar.

- Diatomaceous Earth: Diatomaceous Earth is a fine white powder made from the fossilized remains of tiny, aquatic organisms called diatoms. When anthropods, such as ants, walk over this substance, it penetrates the exoskeleton and dries them out from the inside. You should sprinkle this substance around the colony opening.

- Boiling Water: If you’re looking for a quick and cheap solution, just pour boiling water into the nest. This will kill a majority of the population without eliminating the colony.

- Plant Tansy (Tanacetum vulgare): Tansy, while not a native plant, is commonly found in gardens across the United States. This species will attract pollinators and repel unwanted guests. The plant contains a toxic compound called thujone, which is poisonous to ants; its smell also serves as a repellent. These should be planted near milkweed plants for the most productive results.

Praying Mantis

There is only one species of mantis that is native to the Northeast, the Carolina mantis (Stagmomantis carolina), and there are two invasive species you will likely encounter as well: Chinese mantis (Tenodera sinensis) and the European mantis (Mantis religiosa).

These species are opportunistic, meaning they exploit any available food resource to survive. This includes Monarchs at all stages of development: larvae, caterpillars, and adults. However, this species is generally not a severe threat to Monarch populations. Due to their territorial nature, they often kill other mantises, taking care of the problem for you. If you encounter a mantis in your garden, it’s best to leave it where it is or relocate it to a different area away from your milkweed plants. However, the invasive Chinese species should be eradicated by simply squishing them. Below is a simple guide on how to identify mantis species.

Carolina mantis (Stagmomantis carolina):

Characteristics:

- Color: They come in a variety of colors, including grey, green, and brown. Each color variation can be plain, with stripes or bands, or withspots.

- Sexual Dimorphism:

- Size: Females and males differ in size, with females reaching a maximum length of 3 inches. The males are usually a few centimeters to an inch smaller.

- Wings: Males have longer wings that reach past their abdomens, which allows them to fly. The wings on females do not get to this length, and they are unable to fly.

- Abdomen Size: Females tend to have larger, bulkier abdomens, while males generally do not.

- Leg Spots: They do not have a spot between their front legs.

- Faceplate: The faceplate is short and rectangular.

Chinese mantis (Tenodera sinensis)

Characteristics:

- Color: Green or brown. They lack the spots, bands, and stripes found in the Carolina Mantis, but will come in a distinct color variation in which the body will be brown and the wings green.

- Sexual Dimorphism:

- Size: Females can reach up to 5 inches long, while males only reach up to 3 inches. They are the largest species of mantis found in the United States.

- Wings: Males have longer wings that reach past their abdomens, which allows them to fly. The wings on females do not get to this length, and they are unable to fly.

- Abdomen Size: Females tend to have larger, bulkier abdomens, while males generally do not.

- Leg Spots: They do not have a spot between their front legs.

- Faceplate: The faceplate is longer and square.

European mantis (Mantis religiosa):

Characteristics:

- Color: Green, brown, or yellow.

- Sexual Dimorphism:

- Size: Females can reach lengths of up to 3 inches, while males typically grow to only 2.5 inches. The males also have bigger eyes and longer antennae.

- Wings: Both males and females typically have wings that extend beyond their bodies, allowing both to fly.

- Abdomen Size: Females tend to have larger, bulkier abdomens, while males generally do not.

- Leg Spots: They do have bullseye-like spots between their front legs.

- Faceplate: Triangular and rounder than the Chinese or Carolina mantids.

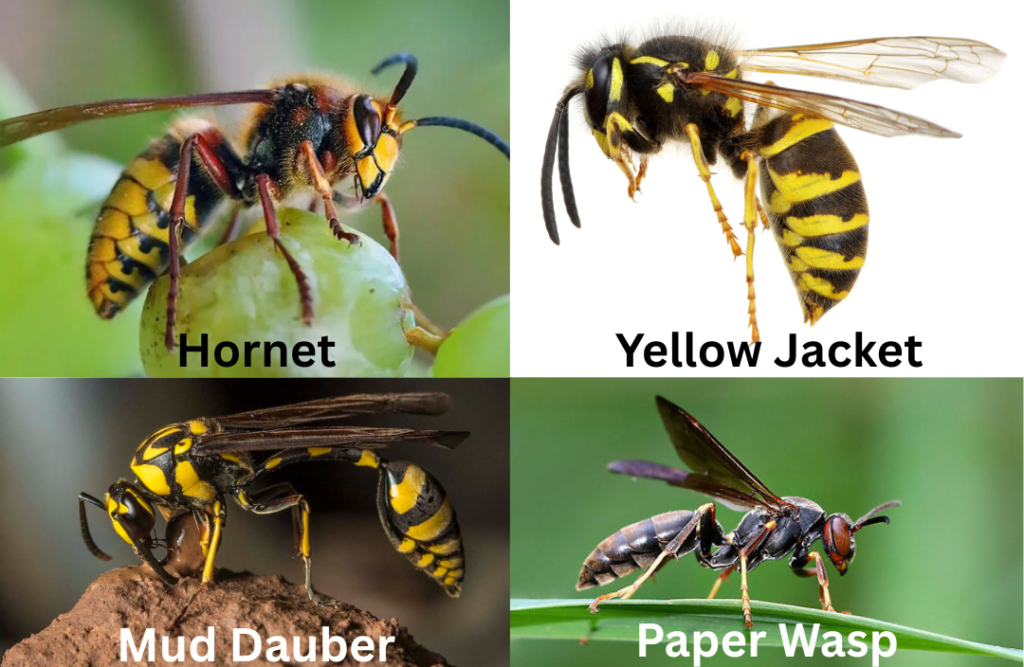

Wasps

Wasps and Hornets are similar creatures; hornets are a type of wasp, along with Mud Daubers and Yellowjackets. Numerous species of both are native to the northeastern United States. The main difference between the two is that wasps are not generally carnivorous, as many feed on nectar and collect flesh to feed their offspring. Hornets, on the other hand, are primarily carnivorous. These little predators are of most concern in urban areas, as there are an abundance of available hideaways to create their nests and plenty of food sources. While they are good pollinators, they pose a danger not only to Monarchs but also to people. Generally, it’s better to remove them from your garden, regardless of the species or type. Several species of parasitic wasps will be discussed in a later section.

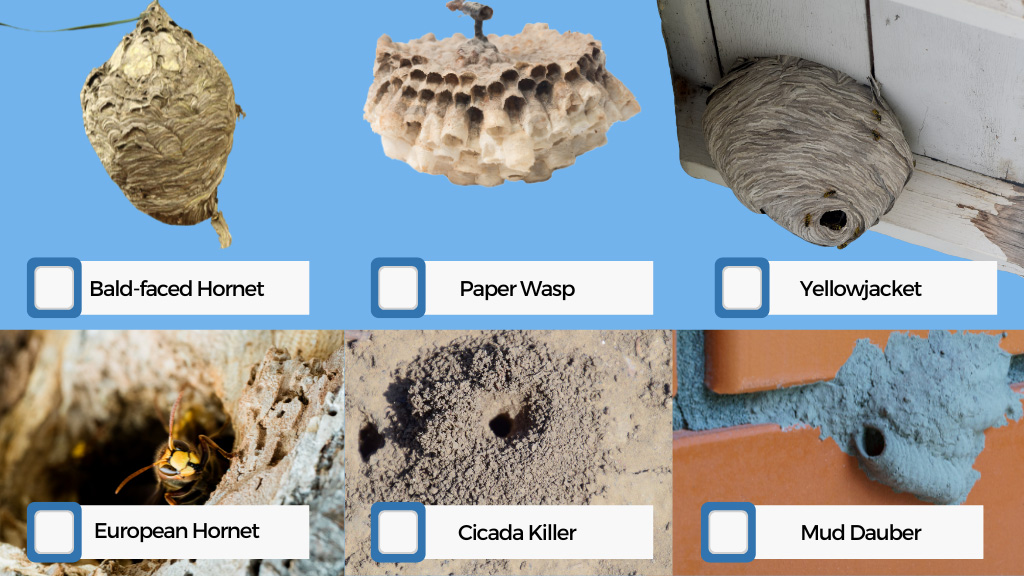

Nest Identification

Hornets make larger, tear-shaped nests that often resemble layered cardboard and can hold up to three to four hundred individuals. These can be found in high places, such as on roof awnings and in trees. Wasps, such as the common paper wasp, can be equally aggressive, so the same level of caution should be used when approaching. These nests are significantly smaller, not enclosed, and can resemble honeycomb. They are highly aggressive, so you should take heavy precautions when removing their nests. Luckily, most species of wasp can be dealt with in the same manner. Mud Daubers make their nests underground, and a professional should be called to remove them.

Fill a bucket about three-quarters full with water and add a dime-sized amount of dish soap. Attach a piece of meat to a board and place it a few inches above the water. Hornets will always launch straight upward when flying, so they will fly directly into the water and drown when they are done eating. You can approach the nest when a good portion of the hornets/wasps are in the bucket. You can either use a spray, which should be applied straight into the nest opening, or slowly approach the nest and place it into a bag, where you are free to destroy it.

Spiders

Spiders are common almost everywhere and are generally not a species to be concerned with; instead, they play a crucial role in controlling other pests. It’s best not to remove them unless they pose a harm to pets or household members. Under certain conditions, however, their populations can grow into infestations.

The best way to prevent infestations is to maintain a tidy garden, free of debris that could act as hideaways. You could also plant flowers with strong odors that act as repellents, like lavender and eucalyptus. Mint is also an option, but it is strongly discouraged due to its ability to rapidly spread and take over gardens.

Ladybugs

Despite their small and unassuming appearance, ladybugs are quite effective predators. Ladybugs will typically prey on Monarchs while they are still in their larval form, before they can sequester cardenolides. However, Monarch larvae are not their main prey; they are only victims of unfortunate circumstances. A ladybug’s preferred food is aphids, which are typically found alongside Monarch larvae on milkweed plants. Oleander aphids (Aphis nerii), or Milkweed Aphids, are small, bright yellow insects that feed on milkweed plants; they are not harmful to the plant or the Monarch larvae/caterpillars. Ladybugs are usually not a species to be concerned about. However, they are prone to overpopulation and infestation.

The best way to avoid having ladybugs decimate your Monarch larvae is not to remove the Milkweed Aphids. Biodiversity is key in all circumstances, and having a variety of species to choose from makes it less likely that ladybugs will choose to prey on Monarch larvae. If there is a ladybug infestation, you will notice. They tend to gather in large swarms within buildings, in which case you should vacuum them. To prevent them from overtaking your garden, you should plant flowers with insect-repelling odors like mums, lavender, and marigolds.

Large Milkweed Bug

The Large Milkweed Bug (Oncopeltus fasciatus) is an herbivorous species that, true to its name, preys on milkweed seeds. But, they are opportunists by nature and sometimes feed on Monarch larvae and eggs. They feed by injecting their saliva into seeds, which predigests and liquifies the innards, which is then sucked out using their straw like tongues (rostrums). They are identifiable by their distinct orange and black colorations that is found in adults and juveniles.

Like Monarchs, this species is migratory and will follow the growth path of milkweed over the course of multiple generations; their arrival varies depending on region, temperature, and abundance.

This species is more of a nuisance than an actual threat, and unless there is an infestation, there is no real need to remove them. In the case of an infestation, avoid using insecticides; instead, gently shake them off into a container of soapy water. It’s also best to maintain a tidy garden, removing leaf litter and debris to decrease the potential for them to overwinter in your garden.

Vertebrates

Rodents

If you live in an urban environment, especially around college/university campuses, where food is plentiful, you will encounter mice and rats. Luckily, rats prefer larger prey and will not go after your Monarchs or milkweed plants. Mice, on the other hand, will occasionally prey on adult monarchs during their migration periods. While many mice avoid eating Monarchs due to their bad taste, the Deer Mouse (Peromyscus maniculatus)occasionally preys on grounded Monarchs. These mice have evolved a similar resistance to cardenolides, a cardiovascular toxin that causes increased cardiovascular activity, as Monarch butterflies. This resistance allows them to consume Monarchs without experiencing the adverse effects of the toxin.

Having a few mice in your garden is not a concern; however, they breed rapidly throughout the year, which can quickly lead to infestations. The best way to avoid overpopulation in your garden is to keep it tidy, clearing leaf litter and large debris that could act as breeding and nesting grounds. The best way to reduce their populations is similar to methods of removing wasps; using a bucket and additional ground traps.

The Bucket Trap:

Take a bucket and either leave it empty (if you plan to relocate the mouse) or fill it halfway with water (for a lethal trap).

- Drill two small holes near the rim of the bucket, directly across from each other.

- Run a sturdy wire or strong string through the holes to create a support across the top of the bucket.

- Attach a flat, lightweight surface—such as a piece of wood or a paper plate (cans also work)—to the wire so that it rests halfway over the bucket. One side should be anchored to the rim so it stays in place, while the other side should hang freely over the center of the bucket, able to tilt or flip under weight.

- Smear a small amount of peanut butter on the edge of the free-hanging side to act as bait.

- Position a stick, wooden slat, or any sturdy object as a ramp, leaning from the floor to the top of the bucket to give the mouse easy access.

When the mouse climbs the ramp and walks onto the baited platform, its weight will tip the loose end, causing it to fall into the bucket. There are a lot of methods to create this trap, and they all work similarly; use what you have on hand, or you can buy one of these traps online.

Lizards/Anoles:

If you’re lucky, your garden will attract anoles or small lizards. For the most part, heavily urbanized areas in the Northeast are unsuitable habitats for anoles, mainly due to the lack of water, suitable breeding grounds, and cold weather. But areas with more undeveloped and overgrown areas, like school campuses, are more likely to attract them. These creatures are becoming increasingly rare, and are effective and natural pest controllers, so it’s not recommended to exterminate them. Instead, if they pose an issue in your garden, it’s best to relocate them.

Some lizard species native to the Northeast United States have a resistance to cardenolides, allowing them to ingest adult Monarchs and caterpillars.

Five-Lined Skink (Plestiodon fasciatus):

- Characteristics:

- Size: Between 5-8 inches

- Color: Colors can vary depending on age. Young skinks will have five distinct lines that run vertically down their bodies, vibrant blue tails, and black bodies. Their strips will become duller with age, and their tails will fade to a grayish hue. Stripe colorations of adult males will change to a dark green or brown, fading into their dark bodies. During mating season, males will also develop bright orange colorations around their mouths.

- Native Range: All Northeast states, except Maine, Massachusetts, and New Hampshire.

- Endangered Status: Endangered in Vermont, threatened in Connecticut, and of great concern in the other nine Northeast states.

Snakes

This den is located in Canada, as Garter Snakes will travel there in the hundreds of thousands to breed.

Snakes are another uncommon species in urban environments, and they are more likely to be found in campus gardens with more open spaces. A snake or two in your garden can be beneficial. Aside from being an adorable feature, they are also excellent at pest control, keeping away unwanted lizards, rodents, birds, and insects.

Multiple species of snakes found in the Northeast include insects in their diets; these snakes will likely be small, slender, and do not pose a danger to humans. Many of these species are also communal, meaning they will coexist within the same territory and share the same den. Their populations can grow rapidly under certain conditions, such as food availability and temperature. The best way to avoid a slithery guest is to keep a tidy garden, removing debris, tall grasses, and open water sources.

The most common species likely to be found in urban gardens are listed below.

Common Garter Snake (Thamnophis sirtalis):

This snake species commonly eats Monarch adults and caterpillars, as they are resistant to the toxin found in their bodies.

Characteristics:

- Size: Up to 36 inches.

- Coloration: Black, gray, green, or brown, with three vibrant yellow stripes running along the length of their bodies. These stripes can occasionally be white or green. Certain subspecies will have red spots along their sides.

- Sexual Dimorphism: Females are larger, with longer tails.

- Other Characteristics: Their head circumference is larger than that of their body, and their scales have a slight lift at the end.

- Native Range: They are found in all U.S. regions, except the southwest.

- Endangered Status: Very common

Eastern Smooth Green Snake (Opheodrys vernalis):

While not resistant to Monarch toxins, they occasionally prey on Monarch adults, caterpillars, and larvae.

Characteristics:

- Size: 14-20 inches

- Coloration: Bright green on the top of their bodies, and a light yellow on the underbelly.

- Sexual Dimorphism: Females are larger and have longer tails.

- Other Characteristics: They have smooth scales that are tight against the body. The head is slightly smaller than the body.

- Native Range: All Northeastern states and some of the Midwest.

- Endangered Status: Very common.

Frogs

Frogs are known for their voracious appetite for insects, and Monarchs of all stages are no exception. Luckily, while they have their place in a frog’s diet, many find them unappetizing due to their body toxins.

The presence of frogs is often an indicator of a healthy and thriving garden, and they are an excellent and natural pest control method. And, to make matters better, it’s unlikely that infestation or overpopulation will occur naturally, as the survival rate of tadpoles is typically relatively low. However, they are still natural predators of Monarchs, and it is important to recognize the most common species.

Northern Leopard Frog (Lithobates pipiens):

Characteristics:

- Size: 2-3 inches long.

- Coloration: Green, brown, or yellowish-green, with a white underbelly and dorsal stripes, and brown spots.

- Sexual Dimorphism: Females are larger. During mating season, males will develop enlarged vocal pouches and enlarged thumbs.

- Native Range: Found across all Northern regions. They tend to stay close to their birthplace, so if your garden is located in a heavily urbanized area without bodies of water, it is unlikely you will encounter them.

- Endangered Status: Not of concern.

Wood Frog (Lithobates sylvaticus)

Characteristics:

- Size: 1.5-3 inches long.

- Coloration: Brown, red, gray, or a combination of each. The females tend to have brighter variations.

- Sexual Dimorphism: The females are larger on average.

- Native Range: They are native to the Northeast and Canada.

- Endangered Status: Not of concern.

Northeastern Green Frog (Lithobates clamitans melanota):

Characteristics:

- Size: 2-3.5 inches in length

- Coloration: Green or brownish-green, with black or brown spots. These spots will appear in a gradient beginning from the upper body and becoming more vivid toward the legs. There is also a rare blue/turquoise variation.

- Sexual Dimorphism: The females are larger, and the males have larger ears (the circles on the side of the head).

- Native Range: Upper Northeast and Midwest regions.

- Endangered Status: Not of concern.

Birds:

Many species of birds will avoid eating Monarchs, repelled by their aggressive coloration and toxins. You should not worry about having them around your milkweed plants. It’s also not recommended to remove them, as they are essential predators and can reduce harmful insects in your garden.

Parasites

Tachinid Flies

The Tachinid fly is the overarching name for a species complex with thousands of subspecies, all of which are parasitic in their larval form. The species Lespesia archippivora is one to watch for, as its primary targets are moth and butterfly caterpillars. Tachinid reproduction involves locating a host, in this case, Monarch caterpillars, and depositing eggs onto them. Females will lay eggs (oviposit) on the anal prolegs (the postieror) of the caterpillar. The eggs take up to three days to hatch, after which they will burrow into the body of their hosts. Over ten to fourteen days, the maggots will consume the innards of the caterpillar, pupate, and emerge as adults. While they appear to be a serious threat on the surface, their removal is not always necessary. As long as a wide variety of insect species are present in your garden, the probability of a fly choosing a Monarch caterpillar is low. The best way to reduce their population is to remove infected caterpillars, effectively stopping a new generation.

Parasitic Wasps

Braconid wasps:

Braconid wasps describe a larger species complex (family) that comprises several thousand subspecies. It’s impossible to narrow down all the specific species that may target Monarchs, but many of the ones that do function similarly. They will either lay eggs on the caterpillar’s body or inject them directly inside using their ovipositors. The wasp larvae will drink the “blood” and internal organs of the caterpillar, growing alongside it. When ready to pupate, they will burrow out of the body and cocoon directly on the caterpillar. The caterpillar is usually alive during this process, but will die soon after the larvae emerge.

Another set of wasps secretes a chemical that changes the brain function of the caterpillar, causing it to protect the wasp cocoons. When the larvae emerge and form cocoons, the caterpillar remains alive and sits on top of the pile to guard them from predators.

Pteromalus cassotis:

This is a small species of wasp in the family Pteromalidae. In contrast to the Braconids, this species specifically targets the chrysalises of Monarch butterflies. They oviposit into the chrysalis of a Monarch pupa, where the wasp larvae feed on its internal organs, and emerge fully grown. The best way to control this species is to remove chrysalises that appear blackened and dead.

Diseases:

Monarchs, like all insects, are susceptible to various pathogens, including viruses, bacteria, fungi, and protozoans. Protozoans are technically a type of parasite, but since they are single-celled organisms, they are included in this section.

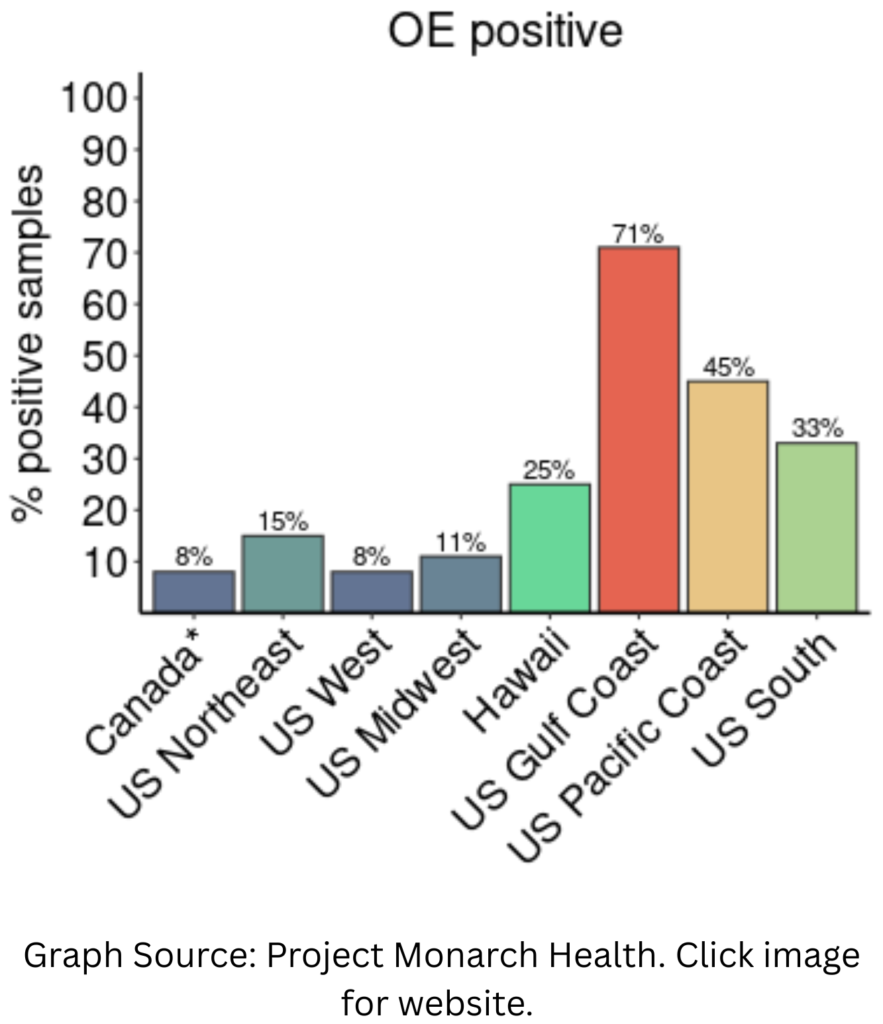

Their long migration patterns take them through multiple regions, facilitating the spread of disease, which creates pathogen commonality throughout the Eastern population. According to studies and Project Monarch Health, the spread of pathogens is more likely in breeding populations. This is due to disease pressure, where the prevalence of a disease in a population increases the longer organisms remain in one place. Pathogen accumulation also occurs when pathogens build up in an environment as the host species remains present for an extended period. During the Monarch breeding period, from late spring to early fall, they stay in one area for multiple generations, allowing pathogens to build up. This phenomenon is best observed in non-migratory populations, like those found in Florida and Hawaii. Luckily, Monarch pathogens are uncommon in the Northeast, but they are still prevalent enough to warrant mentioning.

Identifying infected Monarchs is relatively straightforward, as they will have an “off” appearance. In diseased adults, there are changes in wing coloration around the abdomen, often with a dusty gray appearance. In the case of a fungal infection, white spots will appear on the orange wing section. Diseased caterpillars are easier to identify, as they will appear lethargic, pale in color, emit a greenish goo, or experience anal prolapse. There is also a chance that they will turn completely black before death, or fail to chrysalize, in which case they might develop a large green mass on their heads.

Ophryocystis elektroscirrha:

This species, often shortened to O.E., is a single-celled parasitic protozoan. This is the most common Monarch pathogen in the Northeast. This pathogen spreads through spores transferred from female Monarchs to eggs and milkweed leaves during oviposition. While this pathogen is always lethal, the female only has to live long enough to produce eggs. When spread to eggs and leaves, the spores are dormant and do not begin to infect until larvae and caterpillars digest them. Digestion allows the spores to break open, and the parasites continue to reproduce asexually until the caterpillar forms its chrysalis. At this stage, they will begin to reproduce sexually, and spores will start to form on the outside of their body. Monarchs will emerge infected, usually with noticeable spores and deformities, and the process will begin again.

The best way to prevent the spread is to plant native species, which are perennial and die back during the winter months, only to regrow without spores attached. And if you notice a Monarch adult or caterpillar with any deformities, it should be removed immediately.

Nuclear polyhedrosis virus (NPV)

Nuclear polyhedrosis virus, also known as black death, is a highly infectious and fatal virus that affects Monarch caterpillars and chrysalises. When infected, a caterpillar will become lethargic, darken in color, and begin to liquify. This liquid will leak out of the body and onto milkweed leaves, where healthy caterpillars will consume the virus cells, continuing the cycle. It can also be spread through defecation.

The best way to prevent this virus from decimating your monarchs is to immediately dispose of dead infected caterpillars, which are best identified by their black and deflated appearance. Surrounding leaves should be cut, and, unfortunately, surrounding eggs and larvae should be disposed of.

Pseudomonas bacteria:

This bacterium usually impacts caterpillars and larvae that are already infected with other diseases. It has similar effects to NPV, in which the caterpillar turns black and leaks fluid. It thrives in moist environments, so it’s important not to overwater your garden and maintain good airflow to allow evaporation.

Poisons:

The main poisons you will encounter when creating your gardens are pesticides, herbicides, and insecticides; the most common and widely available of which is Roundup. When ingested, these chemicals disrupt the insect’s nervous system, which negatively affects its ability to function. Depending on the type of chemical, it can cause hyperactivity in the cardiovascular system, paralysis, damage to the reproductive system, or affect the ability to locate food and identify predators.

Setting Up Your Garden:

Hopefully, this guide has prepared you with the necessary background needed to set up your own Monarch-oriented garden.

When designing your garden, you’re likely to encounter three different types that generally serve the same purpose: pollinator gardens, butterfly gardens, and waystations. These work in a hierarchy of ecological intention. Pollinator gardens are the broadest and work to attract and support a wide variety of pollinator species. Butterfly gardens are similar to pollinator gardens, but specifically designed to support butterfly populations. Waystations are similar to butterfly gardens, but they are specifically designed for Monarch butterflies. This guide primarily focuses on creating waystations but can also be applied to supporting Monarch populations in pollinator or butterfly gardens. You can get your waystation certified with Monarch Watch, an organization that works to promote the protection of Monarch populations: Register

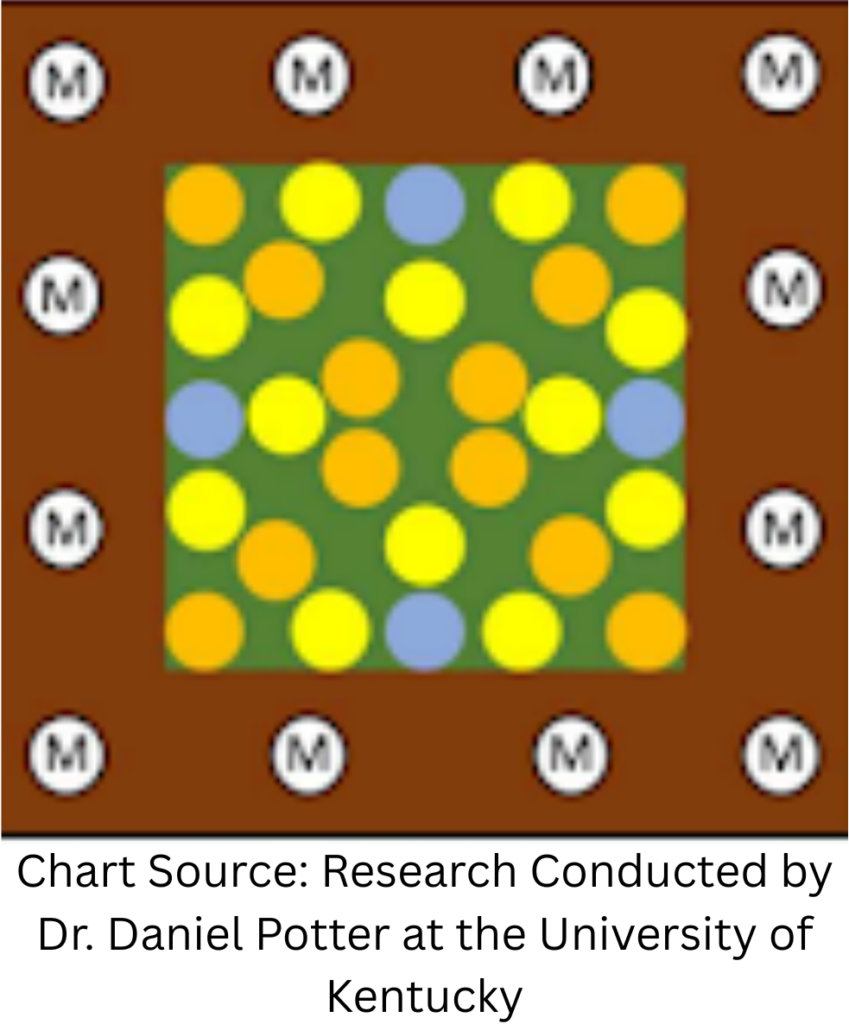

When setting up your waystation, you could go the freeform route, but research has shown that there are benefits to creating a specific layout. Monarchs rely on both smell and sight to find milkweed, but when the plants are overcrowded, it can lower the chances they’ll choose yours for laying eggs; there are also benefits to choosing taller milkweed plants, as they are more visible. Listed are the ideal conditions for your waystation:

No Size Requirement ~ Meaning they are perfect for urban landscapes and school campuses.

- Leave Some Space ~ Leave at least 1 meter between each milkweed plant.

- Don’t Overcrowd! ~ Overcrowding looks pretty, but can deter Monarchs from finding milkweed stems. Plant nectar/decorative plants away from milkweed.

- Bloom Times ~ It’s best to have multiple species of milkweed plants with different bloom times. This ensures that Monarchs have enough resources to sustain them throughout the breeding period. Refer to the section above.

- Think Big! ~ Taller species of milkweed are preferred, as they are more visible to egg-laying Monarchs.

- Keep it native! It’s always best practice to choose native species, as they support local biodiversity and help prevent the spread of invasive species.

- Routine Cutting ~ Monarch caterpillars have an easier time digesting milkweed when they are still green and tender. Trim milkweed plants a few weeks ahead of the breeding season, and continue pruning about once a month throughout the growing season.

- Weed Control ~ Pesticides and Herbicides, like the common Roundup, can decrease the viability or kill caterpillars and milkweed, so hand tending is a must.

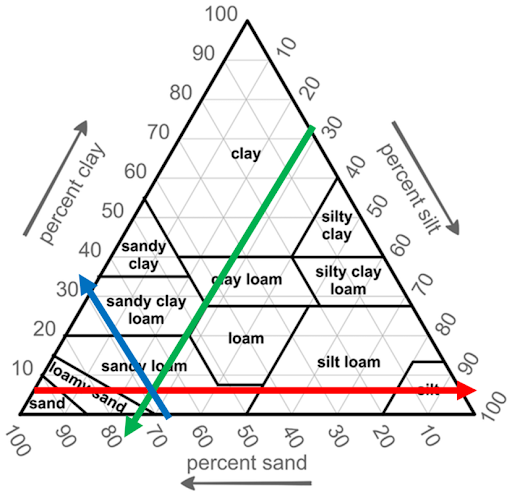

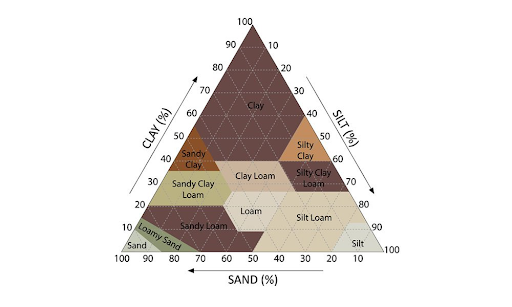

- Location Conditions ~ Certain milkweed species have different soil, moisture, and sunlight conditions. Take these into account when choosing your milkweed species. You can enhance soil quality and moisture by using mulch, store-bought soils, and compost. Below are is the best method to test soil conditions at home:

Checking the characteristics of your soil is easy; just follow these simple steps:

- Fill a jar halfway with the soil you wish to test, and remove large objects such as rocks, leaves, or sticks.

- Fill the jar with water, leaving some air at the top, and shake.

- Leave to settle for at least a few hours, or until the soil has completely separated into different layers and the water has cleared. It will separate into three distinct layers based on density: sand at the bottom, silt in the center, and clay at the top.

- Mark each of these layers on the jar with a permanent marker, and use a ruler to measure the distance between each in millimeters (the small lines on the centimeter side), as well as the total height of all three layers. If the layers are thicker, then measuring in centimeters will work, but generally, millimeters will be more accurate.

- Use this formula to calculate the percentages:

- % SAND=(sand height)/(total height) x 100 =___________ %

- % SILT=(silt height)/(total height) x 100 =____________ %

- % CLAY=(clay height)/(total height) x 100 =____________ %

- Compare these percentages to the chart provided. In most cases, you only need to use two of the percentages, mainly the larger two, but it doesn’t hurt to be as accurate as possible. The spot where all three lines intersect corresponds to the type of soil.